The Effects of Suspending People License Peer Review Article

March nineteen, 2019

More than seven million Americans have had their licenses suspended for unpaid, court-related debts. In most states, a person's driver'south license may be suspended without regard for their power to pay. These policies hit communities of color and people with low incomes the hardest, and tin can result in a wheel of unemployment and inability to pay the outstanding debts, that and so increases exposure to the criminal justice system, all while diverting resources from proven public safety policies.

ACS Issue Cursory AuthorsDanielle Conley and Ariel Levinson-Waldman argue that license intermission schemes are ripe for reform at the state level throughout the country, with many states already leading the way. Designed as a primer on the hazards of license intermission schemes and a resource for advocates and policy makers fighting for reform, the issue brief offers legislative and litigation options for catastrophe these discriminatory policies.

You lot tin download this issue cursory hither.

Discriminatory Driver'south License Suspension Schemes

Issue Brief by Danielle Conley and Ariel Levinson-Waldman

The story of license suspensions . . . reveals both the extent of the injury governments are willing to inflict on low-income people in order to residue their books and the results that advocacy can achieve to reduce the damage. – Peter Edelman[1]

More seven meg Americans have lost their driver's licenses for nonpayment of a ticket or fine.[2] For many lower-income community members in 21st century America, a driver'southward license is critical for everyday life tasks like getting to piece of work, childcare or a child'due south schoolhouse, medico's appointments (particularly vital for senior citizens), and transporting heavy groceries. Most people who are not able to afford to pay their fines, therefore, but go along driving.[three] When a person driving with a suspended license is stopped by law enforcement, they typically get a ticket, may be subjected to more fines, and may even be arrested and end up in prison house. Their inability to pay that original fine—their poverty—is, in effect, criminalized.

National sensation of governments' use of fines and fees to extract revenue from low-income, predominantly African-American residents has risen substantially since the protests and violent conflict that followed the 2014 killing of Michael Dark-brown by the Ferguson, Missouri Police Department. Hither was an object lesson in country and local governmental power to perpetuate and criminalize poverty. Afterwards the U.S. Department of Justice Civil Rights Sectionalization investigated police and court practices in Ferguson, it released a report describing how citizens go trapped in a double helix of poverty and penalization. Initial fines and fees quickly and automatically trigger more than monetary penalties, a suspended driver's license (with more penalties imposed for driving on a suspended license), mandatory court appearances (with more penalties levied for missing those hearings), and, almost inevitably, criminal penalties. The City of Ferguson's "focus on revenue rather than . . . public rubber needs," the report plant, led to "procedures that enhance due process concerns and inflict unnecessary impairment," including the suspension of commuter'southward licenses for unpaid debts, followed ofttimes by an arrest for driving without a license.[four]

In the wake of Ferguson, a wave for reform has emerged. Institutions similar the American Bar Association, for example, have weighed in on this issue, adopting the principle that "disproportionate sanctions, including commuter's license interruption, should never exist imposed for a person's inability to pay a fine or fee,"[5] and explaining that "[e]xcessive fines and fees . . . have burdened millions of Americans, particularly those too poor to pay. The alarming results, including jail time for unpaid traffic tickets, accept effectively criminalized poverty and eroded public confidence in the justice system."[6] And indeed, in the past several years, a growing number of state-level reform efforts have been launched to end license-for-payment schemes in which the legal right to drive is taken away from people for non-payment of fines or fees with no enquiry into their ability to pay.

This Issue Brief examines the policy and legal features of this systemic justice problem and efforts to accost it. Part I sketches out the scope of the problem. Office II explores how license-for-payment schemes: deprive low-income families of coin and opportunity while increasing their exposure to the criminal justice system; disproportionately impact communities of color; forcefulness courts, prosecutors, and police officers to divert resources away from public safety efforts; and, to the extent they exercise generate some revenue for the state government, practice so largely equally a wealth transfer to the state from low-income communities of color who can least beget it. Role III identifies constitutional flaws in license-for-payment schemes and highlights the growing wave of reform that is emerging through legislative action and litigation. A handful of states and now the District of Columbia have taken legislative steps towards reform, and iii federal district courts accept already sustained constitutional challenges to state license-for-payment schemes. Both of these trends are poised to go along. Part IV concludes with some reflections on anticipated reforms and courtroom challenges, and where nosotros go from here.

I. Background

When most people hear near suspended licenses, they think of public rubber issues—drunk driving, for example, or accumulating likewise many points on a driving tape. In contrast to public-condom suspensions, debt-collection suspensions are nigh money, punishment, and coercion—and on a very big scale, at that. Every bit documented by the Legal Assistance Justice Heart, license-for-payment systems are "ubiquitous."[7] In Texas alone, more than 1.viii million people accept had their licenses suspended for unpaid, court-related debts.[8] More than than forty states employ driver's license suspension equally punishment for failure to pay sure debts, which may include traffic or parking tickets, other types of court debt from civil judgments, child back up orders, and taxes or other amounts allegedly owed the land or municipal authorities.[9]

In about states, a person'due south driver's license may be suspended without regard for or inquiry into their ability to pay at the time of intermission.[10] Only 4 states—Louisiana, Minnesota, New Hampshire, and Oklahoma—require a conclusion that the person had the ability to pay and intentionally refused to practice so.[11]

In many states, driver'due south license suspension is a "mandatory result anytime a person does not pay court debt on time."[12] Nineteen states have rules that require commuter'due south license pause following a missed deadline for court debt payment. Of these states, simply New Hampshire requires a court to first make up one's mind that the debtor has the power to pay.[13]

Most jurisdictions that suspend driver'due south licenses for unpaid debt to the government do then indefinitely.[14] In these states, driver'due south licenses remain suspended until the state is satisfied concerning payment (be information technology payment of the full amount or through a negotiated settlement), or until statutes of limitation on debt collection expire, preventing the state from pursuing those debts whatsoever longer.[xv] Merely five states have laws limiting the length of these suspensions,[16] and virtually every jurisdiction imposes an additional fee to reinstate a suspended license.

Failure to pay a fine to the state government, even if it does not pb to the immediate pause of a person'due south license, can, in some jurisdictions, lead to the deprival of a person's application to renew a license, a car registration, or both. Every bit in the break context, the denial of awarding for renewal of the license or registration is automatic and occurs with no research as to the person'due south income or ability to pay.[17] The deprival of the renewal functions, in upshot, as a slow-motion intermission.

II. License-for-Payment Schemes Are Bad Policy

State-level regimes that suspend driver'due south licenses for unpaid debt without requiring an assessment of the individual's ability to pay have a number of negative public policy consequences for the individuals whose licenses are suspended and their families, as well as for the broader community. License suspensions can outcome in reduced job prospects; further inability to pay (or for the government to collect) outstanding debts; and increased exposure to the criminal justice system, which in turn diverts criminal justice resources away from public safety efforts. These consequences unduly fall on our communities of color.

A. Lost Jobs and Reduced Job Prospects

The about direct consequence of widespread license break is decreased employment and income: the loss of a license makes information technology harder to notice or go along a task.[eighteen] A license is "often needed for commuting, particularly as jobs are increasingly located outside of inner-urban center areas; many jobs require driving as function of the work responsibilities; and even for non-driving jobs, employers oftentimes require applicants to have a valid driver'southward license every bit an indicator of reliability or responsibility."[xix] In ane survey, eighty percent of respondents reported not having access to or being unqualified for job opportunities due to license suspensions.[xx]

Studies have plant a robust correlation between a lack of legal authority to drive and unemployment/underemployment.[21] For example, a study of New Bailiwick of jersey drivers establish that 42 percent of individuals whose licenses had been suspended lost their jobs within six months afterward the license interruption, and virtually half were unable to obtain new employment during the pause.[22] And of those drivers that could find some other job, 88 per centum reported a decrease in income.[23] Further, fifty-fifty where employers are willing to hire individuals without commuter'south licenses, a auto remains crucial, as a practical matter, for concrete access to jobs in cities, suburbs, and rural communities. For example, a Brookings Establish report found that only 37 percent of jobs in the D.C. metro area are accessible past public transit inside xc minutes.[24]

Driver's licenses are oftentimes a chore requirement for jobs that tin can lift people out of poverty, such every bit structure, manufacturing, security, transportation, and wedlock jobs.[25] The New Jersey written report constitute that low-income and young drivers were most likely to lose their jobs due to license suspension and too least probable to find some other job.[26] Another written report found that "a valid commuter's license was a more accurate predictor of sustained employment than a General Educational Development (GED) diploma among public aid recipients."[27] The human relationship between mean solar day-to-day mobility and the ability to transition from government assist to employment is likewise well-documented.[28] Put simply, most adults rely on commuter's licenses to travel to work and maintain employment.[29]

B. Decreased Ability to Pay Fines

License suspensions' negative furnishings on employment raises the bones question of why governments would go along to append licenses for unpaid debts. Lisa Foster, a former estimate, former Director of the U.S. Department of Justice Office of Admission to Justice, and electric current Co-Manager of the Fines and Fees Justice Centre, aptly sums information technology upward this style: "If the goal is for people to pay their courtroom debt, why would we make it more difficult for them to get to work?"[30]

If the goal of license-for-payment schemes is to coerce payment of outstanding fines or fees, that logic is flawed when it comes to low-income people. By harming the job prospects and upward mobility of those whose licenses are suspended, license-for-payment laws curtail people's ability to generate the income necessary to repay whatever outstanding fines or fees and to transition away from government assistance.[31] When the government suspends driver's licenses for failure to pay debt, it typically makes debtors less able to pay their fines (a condition which is just exacerbated every bit fines are multiplied by the addition of late fees and license reinstatement fees). The Washington Postal service editorial folio persuasively described the outcome of suspending indigent driver's licenses as: "a fell cycle. Y'all can't afford to pay an initial courtroom fine for a parking ticket . . . so yous lose your license. That means y'all tin't drive to work or hold a job that requires a license—which makes you even less able to pay . . . ."[32]

C. Unnecessary Exposure to the Criminal Justice Organisation

License intermission schemes set up low-income people to suffer the consequences of getting defenseless up in the criminal justice system, as many people who have had their licenses revoked keep driving due to the realities of life.[33] "And if they are stopped by law enforcement, they then become a ticket for driving on a suspended license, which in many states is a misdemeanor. More fines and fees are imposed, and they may exist incarcerated—all because they are poor."[34] As an analysis past the National Briefing of State Legislatures concluded: "All 50 states and the Commune of Columbia . . . have penalties for driving without a license. These penalties vary widely, but follow a like theme: driving without a license is a serious offense that goes beyond a moving violation. Penalties mostly involve fines, jail time or both."[35]

Only as Dahlia Lithwick has observed:

It makes no sense to jail people who are poor for trying to do the very things that could elevator them out of poverty; better to repeal the laws requiring the intermission of driving privileges for non-traffic safety related reasons, than to see it get a one-way road into prison.[36]

D. Disproportionate Bear upon on Communities of Color

License-for-payment schemes are especially problematic because their consequences autumn unduly on low-income communities of color. The criminal justice implications of these schemes are emblematic of this disparity. In an analysis in D.C., for example, where roughly 47 per centum of residents are African-American, over fourscore percent of those arrested in a single twelvemonth for driving without a license were African-American.[37] In Milwaukee, a black driver is 7 times equally likely to exist stopped by police as a white driver, according to an investigation past the Milwaukee Journal-Picket,[38] and two of every three working-age African-Americans do non have a license.[39] An analysis past the ACLU of license suspensions and traffic stops in Ohio concluded that "the loftier constabulary presence in depression-income urban areas likely accounts for this gap. . . . The big picture here is that people's licenses are existence suspended because we take targeted enforcement of laws . . . . Law enforcement officers are often deployed to depression-income communities and communities of colour."[xl]

In jurisdictions with sizable communities of color, the disproportionate affect of license-for-payment schemes extends well beyond criminal law enforcement. In California, African-Americans "are lx percent more likely than non-Hispanic whites to lose their licenses, and Hispanics are twenty percent more likely."[41] Similarly, a 2015 study showed that in Virginia, African-Americans represented nearly 50 percent of the drivers who had their licenses revoked for failure to pay, despite constituting 22 pct of the population.[42]

E. Inefficient Country Revenue Generator

In 2017, then-California Governor Jerry Brown offered a budget bill that ended the suspension of licenses for unpaid traffic tickets. A study accompanying the enacted bill explained that increased fines and penalties "place[] an undue brunt on those who cannot afford to pay," which in California had "led to an increasing amount of fines and penalties going uncollected."[43] The written report concluded that there "does not announced to be a strong connection betwixt suspending someone's commuter'due south license and collecting their fine or penalisation."[44]

Similarly, the Durham County, North Carolina commune attorney found that forgiving the types of traffic debt and court fees that frequently lead to license suspension would not result in lost revenue for the state, noting that "[o]ur research shows that anybody that hasn't paid within two years is not going to pay."[45]

When courts consider a person's income and ability to pay in assessing and collecting fines and fees, nonetheless, the likelihood of collecting that debt are much higher. An assay in Minnesota institute that the land'south diversion airplane pilot program for those with suspended licenses, which immune them to obtain valid licenses while paying fines and fees pursuant to certain minor payment plans, was "responsible for recovering pregnant outstanding fine and fee revenue that would otherwise remain uncollected."[46]

Suspending commuter'due south licenses for unpaid debt winds upwardly costing police and the state departments of motor vehicles significant authoritative and court resource. For case, when Washington State instituted an amnesty program for drivers with suspended licenses, it saved an estimated 4,500 hours of patrol officers' time.[47] And a broad report of pilot programs found that "[a] significant amount of court resources are expended on judicial and administrative oversight of delinquent accounts."[48] Co-ordinate to ane California study, "[t]he police, DMV, and courts spend millions arresting, processing, administering, and adjudicating charges for driving on a suspended license. Add in the price of jailing drivers whose primary fault was failing to pay, and we have a costly debtor's prison."[49]

F. Diversion of Resources from Public Safety

License-for-payment schemes may also create public safety risks. When police force officers and courts become ad hoc debt collectors, their time is diverted from addressing conduct that truly affects public safety. For example, the Washington Land written report estimated that the state devoted more 79,000 personnel hours to dealing with license suspensions unrelated to highway prophylactic. The American Association of Motor Vehicle Administrators determined that "the costs of arresting, processing, administering, and enforcing social non-conformance related driver license suspensions create a significant strain on budgets and other resource and detract from highway and public prophylactic priorities."[fifty]

Further, by reducing employment opportunities, license suspensions may increase the likelihood of recidivism for people coming out of jail and prison,[51] further diverting criminal justice system resource from legitimate public safety concerns to address arrests stemming from the loss of commuter'south licenses that were taken away simply for lack of funds to pay a ticket.

III. A Wave of Reform Efforts

In contempo years, a number of states take taken legislative and authoritative activeness to reform license-for-payment schemes. In parallel, public involvement organizations have brought constitutional challenges to the schemes in a number of jurisdictions; several courts take sustained these challenges, while other litigation efforts have sparked legislative or administrative reform.

A. Legislative and Administrative Reform

In response to the public policy concerns described to a higher place, and further spurred by the high-profile controversies surrounding the fallout from Ferguson, states and cities have begun reforming coercive license-for-payment regimes. Two years earlier Ferguson, Washington Land abolished license interruption for non-moving violations.[52] Since so, California has enacted legislation ending the suspension of commuter's licenses for unpaid traffic tickets.[53] Mississippi, later discussions with advocates, appear that it would both reinstate all licenses suspended for nonpayment of fines, fees, and assessments, and stop suspending licenses for mere nonpayment of court debt.[54] Maine's legislature, over the governor'due south veto, ended automatic driver's license suspensions for many non-driving related fines.[55] Idaho recently enacted legislation decriminalizing driving on a suspended license and ending suspensions for unpaid court fines and fees.[56] And, every bit discussed further below, in 2018, the District of Columbia enacted legislation ending license suspension for failure to pay tickets for moving violations or to announced at a hearing related to such a ticket, and reinstating licenses suspended on those grounds.[57]

States and cities have also implemented a variety of not-statutory programs, policies, and pilots to better license-for-payment laws.[58] The programs include payment plans, some of which are keyed to a person's income,[59] immunity programs that allow people to have their debts reduced or fifty-fifty forgiven,[60] and non-prosecution for driving on a license suspended due to unpaid fines and fees.[61] There are and have been a number of such programs; they were the major source of reform before the post-Ferguson tide of legislative repeal efforts and ramble challenges. Non-legislative reforms, still, are often limited in their telescopic, duration, or efficacy. For example, a payment plan might require a down payment or minimum monthly payment that is prohibitively loftier for people with depression incomes, and in some jurisdictions, drivers who have previously utilized a payment plan cannot constitute another one.[62]

The District of Columbia provides an example of how positive legislative and administrative efforts can movement, more or less, in tandem.

In 2018, the Quango of the District of Columbia (D.C.'s state-level, municipal, and county-level legislature), with support from D.C. Attorney General Karl Racine, enacted a bill that ended the suspension of driver'south licenses for unpaid traffic debts or nonattendance at a traffic court hearing, and required the D.C. Department of Motor Vehicles to restore all licenses suspended on those bases within 30 days.[63] In improver, D.C. enacted a pecker that ends the power of insurance companies to annals a civil courtroom judgment with the mayor and have the accused'southward license suspended until the judgment is satisfied.[64] The affect of these reforms has been significant. According to a D.C. Section of Motor Vehicles report, and as documented by The Washington Mail service, over 65,000 people have had their D.C. driver'due south licenses or driving privileges restored under the at present-legally operative law relating to intermission for unpaid traffic debts or traffic court nonattendance,[65] and an additional 2,282 accept the opportunity to take their licenses restored as of March 13, 2019, when the law pertaining to civil court judgments completed congressional review and took legal outcome.

In parallel to the legislative process, the office of D.C. Mayor Muriel Bowser launched a pilot program to allow residents returning home from prison house with unpaid traffic debt to take their licenses reinstated in commutation for a payment or agreement to a small payment program, noting that "[t]he No. 1 reason for recently released men and women existence re-incarcerated . . . is for driving without a valid license, which also can lead to additional charges for failing to cease and other related crimes."[66] Through this program, an boosted 250 D.C. residents, all formerly incarcerated individuals, have been able to take their licenses restored or renewed by paying "a fraction of the original debt owed."[67]

B. Reform Through the Courts

The Department of Justice'due south report on Ferguson helped catalyze a moving ridge of litigation challenging the constitutionality of license suspension practices. The report did more than than recount the many ways—including driver's license suspensions—that Ferguson's law enforcement and court practices, "shaped past the City's focus on revenue rather than past public safe needs," targeted African-American citizens and especially harmed "those living in or well-nigh poverty."[68] It also explained that these practices raised "significant due process and equal protection concerns."[69] In doing so, the Department identified practices that required firsthand attention and also suggested a blueprint for challenging those practices in court.

Lawsuits are now pending in Alabama, California, Michigan, Montana, Pennsylvania, North Carolina, Oregon, Tennessee, and Virginia.[lxx] The challenged land practices differ somewhat, just what they all take in mutual is that they either automatically suspend a person'south license or otherwise fail to consider a person's ability to pay the fines or fees that trigger intermission. Four legal theories, all of which share mutual nuclei in the Constitution's equal protection and due process clauses, underlie these challenges.[71] Two of these theories are familiar to most lawyers: procedural and substantive due process. The remaining two theories depict from longstanding but less familiar Supreme Court precedent limiting the country'south power both to punish individuals for being unable to pay regime-owed debt and to employ unduly harsh methods when attempting to collect that debt; these overlapping claims are often referred to by the key decisions in the instance line: Bearden 5. Georgia[72] and James five. Strange.[73]

The following sections provide an overview of these claims, focusing on five cases pending in federal district court, none of which have yet to be addressed on the merits in an opinion past a federal appellate courtroom: Fowler v. Johnson in the Eastern District of Michigan; Stinnie v. Holcomb, in the Western District of Virginia; Robinson five. Purkey and its companion case, Thomas 5. Haslam, in the Middle District of Tennessee; and Mendoza 5. Garrett, in the District of Oregon. These courts take diverged in their treatment of the four major claims, resulting in complete victory in Robinson and Thomas, preliminary success on only the procedural due process claims in Fowler and Stinnie, and complete dismissal in Mendoza. The forcefulness and contours of these claims remain in flux every bit the cases await future claim consideration by the courts of appeal.

1. Procedural Due Process

Nearly of these cases include a procedural due process merits alleging that the challenged practices provide inadequate pre-deprivation procedural protections—at minimum, observe and opportunity to be heard.[74] The Supreme Courtroom's decision in Bell five. Burson is the touchstone for these claims.[75] In Bell, the Supreme Courtroom recognized that "[s]uspension of issued [driver's] licenses thus involves country action that adjudicates important interests of the licensees" and held that "[i]north such cases the licenses are non to exist taken away without that procedural due process required past the Fourteenth Amendment."[76]

Fowler and Stinnie provide examples of (thus far) successful procedural due process challenges. The Fowler court held that Michigan provided inadequate discover of the consequences of nonpayment of a traffic ticket, the right to asking a hearing, and the availability of alternatives to full payment; did not provide sufficient time for a response earlier suspension; and failed to provide a meaningful pre-suspension inquiry into a person'south ability to pay.[77] More than recently, the Stinnie courtroom preliminarily enjoined enforcement of Virginia's license suspension for court debt statute on similar grounds:

At no time are Plaintiffs given any opportunity to exist heard regarding their default, nor practise they have the opportunity to nowadays evidence that they are unable to satisfy court debt. This is non sufficient in light of the 'degree of potential deprivation that may exist created.' [78]

2. Substantive Due Procedure

The plaintiffs in these suits as well raised substantive due process claims, asserting that the challenged practices are not rationally related to legitimate regime objectives.[79] Although rational footing review is ofttimes viewed as "minimal scrutiny in theory and virtually none in fact,"[80] the commune courtroom decisions in Robinson and Thomas nonetheless held that Tennessee'southward constabulary failed even that low standard considering information technology was both ineffective—"because no person tin can be threatened or coerced into paying coin that he does non have and cannot get"—and "powerfully counterproductive"—because it "demolition[d]" the state's chances of actually collecting the coin that the law was supposed to help it collect.[81] In contrast, the Fowler and Mendoza courts awarding of rational basis review led them to sustain Michigan and Oregon'south license pause laws, respectively, against a substantive due process merits.[82]

3. Proscription Against Punishing Poverty

Suits challenging the license suspension regimes also draw from the Supreme Court'southward decision in Bearden, which held that a state could not revoke probation solely because a person had failed to pay a fine or restitution.[83] Bearden ended that the country must find that the "probationer willfully refused to pay or failed to make sufficient bona fide efforts."[84] To do otherwise "would be little more punishing a person for his poverty."[85] Following a thirty-twelvemonth line of established cases ensuring indigent criminal defendants' access to courts and limiting the state's power to penalize those unable to pay fines or restitution, the Court refused to allocate its analysis co-ordinate to traditional equal protection and due process categories. It explicitly eschewed, for example, applying a tier of scrutiny—rational basis, intermediate, or strict—noting that "[d]ue procedure and equal protection principles converge in the Court's analysis in these cases."[86]

The legal framework for analyzing a Bearden claim in the license-for-payment context is still developing. At that place is meaningful variation in litigants' approaches and jurisdiction-specific case police, and it is possible that multiple standards will emerge. For example, although Bearden itself rejected a level-of-scrutiny arroyo that characterizes many constitutional claims, the district court in Robinson ruled that it was jump by 6th Circuit precedent to apply rational-footing review.[87] But the commune courtroom'southward opinion in Robinson is forceful enough to suggest that license-pause schemes might run afoul of overlapping theories of harm:

[T]aking an private's driver's license away to try to make her more likely to pay a fine is not using a shotgun to do the task of a rifle: information technology is using a shotgun to treat a broken arm. At that place is no rational basis for that.[88]

Recently, the same judge expanded on her opinion in Robinson, concluding that Bearden was not limited to protecting only fundamental rights.[89]

In contrast, Mendoza concluded that nether its reading of Bearden, that authority applies only where "either incarceration or access to the courts, or both, is at pale," finding that the plaintiffs had not demonstrated that their challenge to Oregon's law suspending licenses for unpaid traffic debt was likely to succeed considering "[northward]one of those rights or interests are present hither."[ninety]

4. Prohibition on Unduly Harsh or Discriminatory Debt Collection Tactics

Challenges to license interruption schemes likewise enhance another claim, fatigued from the Supreme Court'due south decision in James v. Strange: When the regime is acting every bit a debt collector, it cannot apply its power to "impose disproportionately harsh or discriminatory terms merely considering the obligation is to the public treasury rather than to a private creditor."[91] The argument that license interruption without an indigency exception is an "disproportionately harsh" collection tactic that also discriminates against the poor can be compelling.[92] The court in Thomas granted summary judgement for the plaintiffs on their Strange claim, concluding that

the [police force] at issue in Foreign was … unconstitutional because it singled out debtors who owed money to the government . . . and imposed on them uniquely harsh collection mechanisms in 'such discriminatory fashion' that it 'blight[ed]' the 'hopes of indigents for self-sufficiency and self-respect.' That is exactly what [the Tennessee law] by failing to have an exception for indigence, does likewise.[93]

Fowler, by contrast, found that the Michigan statute did non expressly eliminate whatever "exemptions normally bachelor to judgment creditors" and therefore did non violate the Equal Protection Clause.[94] Mendoza, which rejected the Strange claim, agreed, and additionally concluded that the statute was likely to survive rational basis review.[95] Thus, though there is strength to applying Strange to license-suspension laws (equally is the instance with the due process and Bearden arguments), it remains to exist seen whether—and under what facts—a Strange claim volition ultimately prevail.

Iv. Where We Go from Hither

In coming years, several developments may grow out of the recent reforms of state and local license-for-payment schemes. More states and municipalities are poised to cease or curtail automated license suspensions for unpaid traffic tickets and other fines and fees.[96] Thus-far-unsuccessful legislative reforms in jurisdictions like Florida, Minnesota, and Virginia, nonetheless made substantial progress through the legislative process.[97] These jurisdictions may well see a continued push for legislative reform. In late 2018, for example, Virginia's governor proposed legislation ending license suspensions for unpaid court costs and fees, noting that "Ofttimes, people don't pay court costs because they tin't afford it. Suspending their license for these unpaid fees makes it that much harder on them."[98]

Jurisdictions that practice non reform these practices by legislation or executive action face up a substantially increased likelihood of legal challenge. In addition to the litigation approaches discussed in a higher place, two other areas relatively unexplored in litigation may meet increased focus. Starting time, jurisdictions that bar a person from renewing their license until they pay outstanding fines, fees, or other amounts allegedly owed to the government may well have litigation exposure. The same legal principles that persuaded several courts that license suspensions without any such inquiry are unconstitutional would seem to apply equally to the deprival of license renewals without any such research. To the extent these schemes function in effect as deadening-motion suspensions for unpaid debts, the ultimate harm is materially the same, equally the individual who cannot pay loses access to the benefits of lawfully driving to work and engaging in other key 24-hour interval-to-day life activities.

2d, Bearden, Bong, and similar precedents would likewise seem to apply to suspensions from unpaid child back up orders. Federal statutory law requires all states to adopt "[p]rocedures under which the State has (and uses in appropriate cases) authority to withhold or suspend, or to restrict the use of commuter's licenses . . . of individuals owing overdue support or declining, later on receiving appropriate discover, to comply with subpoenas or warrants relating to paternity or child support proceedings."[99] Those states with child support-based intermission schemes that do not examine, prior to suspension, whether the non-custodial parent can pay, may be vulnerable to claims similar to the due process and equal protection challenges described above apropos suspensions from unpaid fines and fees.[100]

***

More than than forty states have statutes that, in consequence, use driver's license intermission or renewal denial to coerce payment of debts allegedly owed to the government. Most of these statutes contain no safeguards to distinguish between people who intentionally reject to pay and those who default due to poverty. They punish both groups as harshly, as if they were as blameworthy. They are not. Our laws should non penalize or criminalize poverty. The good news is that we are seeing a wave of reform addressing this systemic problem through state legislatures and in courts. With the help of engaged, fair-minded citizens, lawyers, and policy makers, nosotros tin can expect that wave to grow.

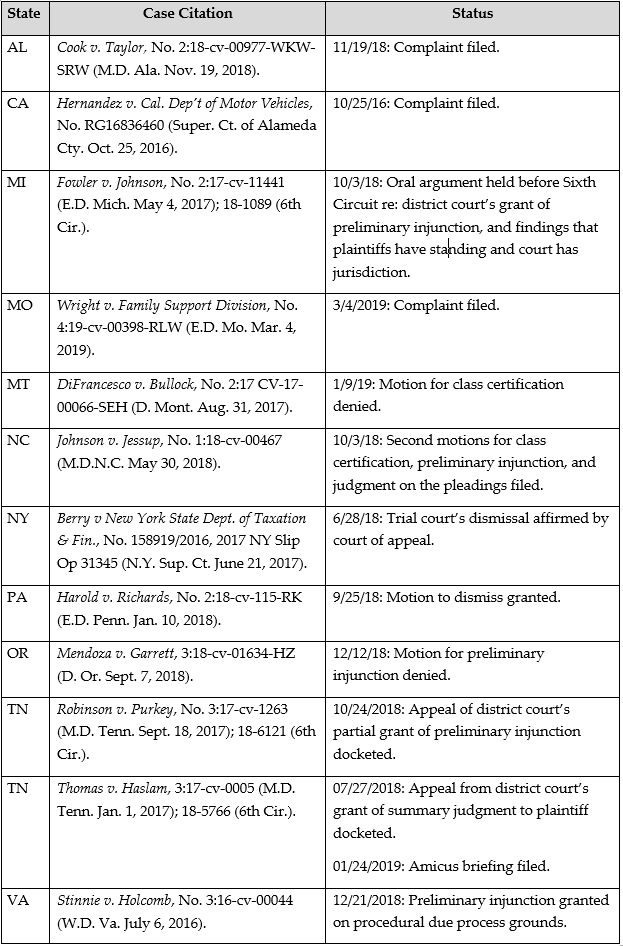

APPENDIX:

Awaiting Cases Challenging License-for-Payment Schemes

About the Authors

Danielle Conley is a partner at WilmerHale and co-chair of the firm'southward Anti-Bigotry Practice. She served as Associate Deputy Attorney General at the U.S. Section of Justice nether Chaser Full general Loretta Lynch and Deputy Attorney General Emerge Q. Yates. Danielle serves on the Advisory Counsel of Tzedek DC and leads a pro bono squad at WilmerHale that co-counsels with Tzedek DC in connexion with efforts to reform license-for-payment schemes in the District of Columbia.

Ariel Levinson-Waldman is the Founding Director of Tzedek DC, a public interest center headquartered at the University of the District of Columbia (UDC) David A. Clarke Schoolhouse of Constabulary that works to safeguard the rights and interests of depression-income D.C. residents facing debt-related problems. He served under U.South. Secretary of Labor Thomas Perez as an Counselor to the White Firm Legal Aid Roundtable, and before that in land and local government every bit the Senior Counsel to District of Columbia Attorney Generals Irvin Nathan and Karl Racine. He practiced before in his career at WilmerHale and has taught courses at UDC and at the Georgetown University Police force Heart.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to extend special thanks for: critical contributions to the Issue Brief by Matthew Robinson and Leah Schloss of WilmerHale and former Tzedek DC Beau Rebecca Azhdam; review of and insightful suggestions on an earlier draft by Peter Edelman, Irvin Nathan, Lisa Foster, Joanna Weiss, Janet Lowenthal, and Mark Kahan; insights on client experiences from Tzedek DC Acquaintance Director Sarah Hollender; and key enquiry assistance past University of the Commune of Columbia David A. Clarke School of Law students LaNise Salley, Class of 2019, and Elsie Daniels, Grade of 2020, as well as former Tzedek DC Boyfriend Rachel Gray.

Well-nigh the American Constitution Society

The American Constitution Club (ACS) believes that law should be a force to ameliorate the lives of all people. ACS works for positive modify past shaping debate on vitally important legal and ramble issues through evolution and promotion of loftier-bear on ideas to opinion leaders and the media; past building networks of lawyers, law students, judges and policymakers dedicated to those ideas; and by countering the activist conservative legal movement that has sought to erode our enduring constitutional values. By bringing together powerful, relevant ideas and passionate, talented people, ACS makes a divergence in the constitutional, legal and public policy debates that shape our democracy.

[1]Peter Edelman, Not a Crime to exist Poor: The Criminalization of Poverty in America 40 (The New Press 2017).

[two] Justin Wm. Moyer, More than 7 Million People May Have Lost Commuter's Licenses Because of Traffic Debt, Wash. Post (May xix, 2018) ("The total number nationwide could be much college based on the population of states that did not or could not provide information."). This number was derived from a single snapshot in time published in 2017. Id.

[3] See, eastward.g., Nat'l Highway Traffic Safety Admin., U.S. Dep't of Transp., Effectiveness of Administrative License Suspensions and Vehicle Sanction Laws in Ohio (2000) (noting estimates that "upwardly to 75% of DUI offenders go on to bulldoze while suspended").

[iv] Civil Rights Div., Dep't of Justice, Investigation of the Ferguson Law Department 2 (2015).

[v] Run across X Guidelines on Court Fines and Fees § 3 cmt. (Am. Bar Ass'n 2018).

[6] Id. at 4.

[7] Mario Salas & Angela Ciolfi, Legal Assist Justice Ctr., Driven By Dollars 8 (2017). Only 4 states (California, Kentucky, Georgia, and Wyoming)—do not suspend commuter's licenses for unpaid courtroom debt. See id.

[8] See Andrea Chiliad. Marsh, Nat'l Ctr. for Courts, Rethinking Driver'due south License Suspensions for Nonpayment of Fines and Fees 21 (2017).

[9] Salas & Ciolfi , supra note seven, at 8.

[10] Id.

[11] Id.

[12] Id.

[13] Id. at viii, 13 n. 38 (citing N.H. Rev. Stat. § 263:56-a).

[fourteen] Run into id. at xiv-15.

[fifteen] Even where the judgment has expired, however, and the police requires reinstatement of the license, DMV bureaucracies may neglect to promptly restore the license. See, east.chiliad., Performance Oversight Hearing Regarding the Section of Motor Vehicles: Hearing Before the Commission on Transportation and the Environment , Council Period 22, 2 (D.C. 2018) (statement of Stacy Santin, Staff Attorney, Legal Aid Club of the District of Columbia) ("One common and problematic scenario we meet involves the continued license suspension based on a judgment that has already expired.").

[sixteen] See Salas & Ciolfi, supra annotation 7, at 9. United states of america with laws limiting the length of suspensions are Idaho, Minnesota, New United mexican states, Vermont, and Wisconsin. Id.

[17] See, e.g, Hawaii (H.C.T.R. Rule 15(b)), Illinois (625 I.50.C.S. § five/6-306.6); Texas (Tex. Transp. Code Ann. §§ 706.002, 706.004); DC Official Code §§ 47-2861 (D.C.'s so-called "make clean-hands constabulary," under which an applicant for a license renewal will be denied if $101 or more is owed to the DC government for, among other things, any fine, punishment, interest, or taxation).

[18] Run into, due east.g., Alex Bough, et al., Lawyers Comm. for Civil Rights of the San Francisco Bay Area, Not Just a Ferguson Problem: How Traffic Courts Bulldoze Inequality in California seven (2015).

[nineteen] Id. at 17.

[20] Margy Waller, Jennifer Doleac, & Ilsa Flanagan, Brookings Inst., Driver's License Break Policies 2 (2005).

[21] Encounter, eastward.yard., Bender et al., supra annotation 18, at 17 n.70 (collecting studies).

[22] North.J. Motor Vehicles Affordability and Fairness Task Force, Final Written report 38 (2006) [hereinafter N.J. Motor Vehicles].

[23] Id. Further, chore losses resulting from loss of driving privileges can accept a cascading toll effect, with the economic costs of unemployment or job switches sometimes existence transferred onto the employers. As one California study found, "there is a cost to hiring and re-grooming a new person for a job existence washed well by someone else. It is an unnecessary expense to both employers and the state to pay unemployment insurance for an employee who would exist retained if the person had a license." Bough et al., supra notation 18, at 7.

[24] Adie Tomer, et al., Metropolitan Policy Programme at Brookings, Missed Opportunity: Transit and Jobs in Metropolitan America 16 (2011).

[25] Alana Semuels, No Driver's License, No Job, Atlantic (June xv, 2016).

[26] See N.J. Motor Vehicles, supra note 22, at 38.

[27] Rebekah Diller, Brennan Ctr. for Justice, The Hidden Costs of Florida'south Criminal Justice Fees 20-21 (2010) (citing John Pawasarat & Lois M. Quinn, Employment & Training Inst., Univ. of Wis. Milwaukee, The EARN (Early on Assessment & Retention Network) Model for Effectively Targeting WIA & TANF Res. To Participants (2007)).

[28] Encounter, e.g., U. S. GAO, Welfare Reform: Transportation's Office in Moving from Welfare to Work (1998).

[29] Id.

[30] Lisa Foster, Lecture at the 59th Miller Distinguished Lecture Series at Georgia State University Higher of Police force: Injustice Under Police force: Perpetuating and Criminalizing Poverty Through the Courts (Mar. 2, 2017).

[31] Bender et al., supra note eighteen at 7 ("[B]y restoring commuter's licenses and allowing people to work, more drivers would be able to pay traffic fines and fees, which would reduce uncollected court debt and increase revenue.").

[32] Editorial Board, Virginia is Punishing the Poor—and Perpetuating Their Poverty, Wash. Postal service, (Feb. v, 2018).

[33] Thomas B. Harvey, Jailing the Poor, 42 Hum. Rts. Mag. sixteen (2017).

[34] Lisa Foster, Injustice Nether Police force: Perpetuating and Criminalizing Poverty Through the Courts, 33 Ga. St. U. L. Rev. 695, 708 (2017); meet too Ariel Levinson-Waldman & Joanna Weiss, D.C. Should Stop Suspending Driver'south Licenses for Unpaid Fines , Wash. Post (Aug. 19. 2018) ("No one should have to risk incarceration considering he or she needs to drive to piece of work, pick upward kids or rush a family unit member to the hospital.").

[35] Driving While Revoked, Suspended or Otherwise Unlicensed: Penalties past Land , Nat'50 Conf. St. Legislatures (October. 27, 2016). Future enquiry is warranted on the number of people arrested for driving on a suspended or revoked license where the license was stripped due to unpaid debts.

[36] Dahlia Lithwick, Punished for Existence Poor, Slate (July sixteen, 2016).

[37] The "Commuter's License Revocation Fairness Amendment Act of 2017" (22-0618) : Hearing Earlier the Committee on Transportation and the Environment, Quango Period 22 (D.C. 2018) [hereinafter Banks Testimony], (statement of Marques Banks, Equal Justice Works Fellow, Washington Lawyers' Commission for Ceremonious Rights and Urban Affairs).

[38] Ben Poston, Racial Gap Found in Traffic Stops in Milwaukee, Milwaukee J. Picket (Dec. 3, 2011).

[39] Jessica Eaglin, Commuter's License Suspensions Perpetuate the Challenges of Criminal Justice Debt, Brennan Ctr. for Simply. (Apr. thirty, 2015).

[xl] Sara Dorn, License Suspensions Disproportionately Imposed on Poor Ohioans, Trapping Them in Debt, Cleveland.com (Mar. 31, 2017) (internal quotations omitted) (describing report past ACLU of Ohio).

[41] Edelman, supra note 1, at 38.

[42] Banks Testimony, supra notation 37.

[43] California AB 103 – Public Safety Double-decker, Fines and Fees Simply. Ctr. (June 27, 2017).

[44] Id. (emphasis added)

[45] Virginia Bridges, Why is Durham Dismissing Hundreds of Speeding Tickets, with Thousands More Expected?, Herald Sun (Jan. 17, 2019) (internal quotation marks omitted).

[46] Driver & Vehicle Servs., License Reinstatement Diversion Airplane pilot Plan, Legislative Report 9 (2013) (Minnesota Driving Diversion Program).

[47] Shaila Dewan, Commuter's License Suspensions Create Cycle of Debt, N.Y. Times (April. fifteen, 2015).

[48] See Beth A. Colgan, Graduating Economic Sanctions According to Ability to Pay, 103 Iowa L. Rev. 53, lxx (2017).

[49] Bender et al., supra note 18, at 7.

[l] Am. Ass'n of Motor Vehicle Adm'rs, Best Practices Guide to Reducing Suspended Drivers 2 (2013).

[51] See Kevin T. Schnepel, Good Jobs and Recidivism , 128 Econ. J. 447 (2016).

[52] See Eaglin, supra note 39.

[53] California No Longer Will Suspend Commuter'southward Licenses for Traffic Fines , L.A. Times (June 29, 2017 9:50 AM).

[54] SPLC, MacArthur Justice Center, and Department of Public Safety Announce that Mississippi Will Reinstate Thousands of Driver's Licenses Suspended for Failure to Pay Fines, U. Miss. Sch. L. (Dec. xix, 2017).

[55] LD 1190 (HP 827) 128th Leg, (Me. 2017) (Engrossed by the House on June 23, 2017 and past the Senate on June 27, 2017; Veto Override on July ix, 2018). Maine police force previously provided that failure to pay any monetary fine imposed by a court for a ceremonious violation, traffic infraction proceeding, or sentence for a criminal conviction could subject a defendant to license suspension. Me. Rev. Stat. Ann. tit. 14, § 3141 Under the recently-passed bill, license interruption was removed from this regime. Id. Virginia also enacted legislation to provide payment plans to people at take a chance of losing their licenses because of court debt, see Travis Fain, McAuliffe Sign Bill on Drivers License Suspensions, Daily Press (May 25 ,2017, 8:11 PM), only that reform has been criticized as ineffective, run across Legal Aid Justice Ctr., Driving on Empty: Payment Plan Reforms Don't Fix Virginia's Court Debt Crisis (2018).

[56] H.B. 512, 64th Leg., 2d Sess. (Idaho 2018).

[57] See D.C. Human activity 22-449 (amending D.C. Law ii-104; D.C. Code § 50-2301.01 et seq.); meet likewise notes 59 - 61 and accompanying text.

[58] In add-on to the types of programs described in the body text, some jurisdictions let individuals to perform community service in lieu of payment. Run across, east.g., Alicia Bannon, Mitali Nagrecha, & Rebekah Diller, Brennan Ctr. for Justice, Criminal Justice Debt: A Barrier to Reentry 11 (2010); Richard A. Webster, $23,000 in Traffic Fines Reduced to $9 for Human being equally Pilot Program Takes on New Orleans' Court System , NOLA.com (Mar. thirty, 2017) (New Orleans); run across generally Andrea K. Marsh, Nat'50 Ctr. for Courts, Rethinking Driver's License Suspensions for Nonpayment of Fines and Fees (2017). Customs service programs are oft non feasible for people earning a depression income. Typically, community service is credited at minimum wage or $10 per 60 minutes, which means that anyone working multiple jobs or carrying significant family obligations cannot feasibly observe the dozens or even hundreds of hours required to satisfy even a fairly modest corporeality of courtroom debt. Some of these programs also require fees for participation (e.g., to encompass the administrative costs of the programme), which are oft sufficiently high equally to defeat the purpose of using the programme to aid those who cannot afford the monetary fees. See, due east.m., Community Service Program, Southward.F. Mun. Transp. Bureau, (listing enrollment fees of upward to $125).

[59] See, e.g., Driver & Vehicle Servs., supra note 46; Megan Cassidy, Tin't Get Your Phoenix Driver'due south License Back Because of Fines? Court Program Can Help, Az. Cent. (Jan. 27, 2016) (Phoenix, Arizona Compliance Assist Programme).

[60] Encounter, eastward.g., Durham Commuter Amnesty Programme, Fines and Fees Just. Ctr. (November. 27, 2017).

[61] Adam Tamburin, Prosecutor'southward New Plan for Commuter's License Violations Could Keep 12,000 Cases Out of Courtroom , Tennessean (Sept. 4, 2018); Yolanda Jones, Shelby Canton DA's Part Won't Prosecute Many Revoked Driver's Licenses Cases , Daily Memphian (Oct. twenty, 2018, four:00 AM).

[62] See Vinnie Rotondaro, Traffic Tickets: the District Profits and Residents Pay, Launder. Urban center Paper (Sept. 13, 2018) (noting that "[d]rivers are currently only allowed one-time access to a payment program where tickets can be paid in installments" in D.C.).

[63] 66 D.C. Reg. 590 (Jan. xviii, 2019); run into also Reis Thebault, In D.C., No More License Suspensions for Drivers with Unpaid Tickets, Wash. Post (July 12, 2018); D.C. Enacts Tzedek DC-Championed Driver'due south License Suspension Reform Bill, UDC/DCSL (Sept. 10, 2018).

[64] 66 D.C. Reg. 590 (Jan. 18, 2019) (bill pending congressional review).

[65] See Justin Wm. Moyer, D.C. Restores Driving Privileges for More than Than 65,000 People, Wash. Post (February. 27, 2018).

[66] Beth Schwartzapfel, 43 States Suspend Licenses for Unpaid Court Debt, Simply That Could Change , Marshall Project (November. 21, 2017) (quoting the Part of D.C. Mayor Muriel Bowser).

[67] Press Release, Office of Mayor Muriel Bowser, Mayor Bowser's Pathways to Work Reentry Program Hits Milestone of 250 Residents Helped (Oct. 4, 2018).

[68] Civil Rights Div., Dep't of Justice, supra notation 4, at 2, four.

[69] Id. at 55.

[seventy] See Complaint, Robinson five. Purkey, No. three:17-cv-1263 (M.D. Tenn. Sept. 18, 2017); Complaint, DiFrancesco v. Bullock, No. CV-17-66-BU-SEH (D. Mont., Aug. 31, 2017); Complaint, Fowler v. Johnson, No. 2:17-cv-114411 (East.D. Mich. May iv, 2017); Complaint, Thomas 5. Haslam, No. 3:17-cv-00005 (M.D. Tenn. Jan. 4, 2017) (currently pending in the Sixth Circuit, see Thomas v. Haslam, No. 18-5766 (6th Cir. July 27, 2018)); Complaint, Hernandez v. Cal. Dep't of Motor Vehicles, No. RG16836460 (Super. Ct. of Alameda Cnty., Oct. 25, 2016) (California); Outset Amended Complaint, Stinnie v. Holcomb, No. three:16-cv-00044 (Westward.D. Va. July vi, 2016); Complaint, Harold 5. Richards, No. ii:xviii-cv-00115-RK (E.D. Penn. Jan. 10, 2018); Complaint, Mendoza v. Garrett, No. 3:18-cv-01634-HZ (D. Or., filed Sept. eight, 2018).

[71] For a helpful additional overview of the emerging legal theories underlying challenges to license for payment laws, see Nat'l Consumer Constabulary Ctr., Against Criminal Justice Debt (2016).

[72] Bearden v. Georgia, 461 U.S. 660 (1983).

[73] James v. Foreign, 407 U.South. 128 (1972)

[74] See, e.chiliad., DOJ Statement of Involvement at 6, Stinnie five. Holcomb, No. 3:sixteen-cv-00044, 2017 WL 963234 (W.D. Va. Mar. 13, 2017) ("A driver's license is a protected interest that, one time issued, cannot exist revoked or suspended 'without that procedural due process required by the Fourteenth Amendment.'") (quoting Bell v. Burson, 402 U.Southward. 535, 539 (1972)).

[75] Bell, 402 U.S. at 535.

[76] Id. at 539; see besides Cleveland v. U.S., 531 U.S. 12, 26 n. 4 (2000) ("In some contexts, nosotros have held that individuals have constitutionally protected property interests in state-issued licenses essential to pursuing an occupation or livelihood. See, e.g., Bell v. Burson, 402 U.S. 535, 539 (1971) (commuter's license).").

[77] Fowler 5. Johnson, No. ii:17-cv-114411, at *27-31 (E.D. Mich. May 4, 2017).

[78] Stinnie 5. Holcomb, NO. 3:16-CV-00044, 2018 WL 6716700, at *9 (Due west.D. Va. Dec. 21, 2018).

[79] See, east.1000., Robinson v. Purkey, No. 3:17-cv-1263, 2017 WL 4418134 at *8 (Yard.D. Tenn. Oct. v, 2017) ("Information technology is therefore difficult to discern the rational basis for the aspect of the scheme that Robinson and Sprague have challenged—the lack of an exception for the truly indigent.").

[80] Gerald Gunther, Foreword: In Search of Evolving Doctrine on a Changing Court: A Model for a Newer Equal Protection, 86 Harv. L. Rev. one, 8 (1972).

[81] Thomas five. Haslam, 329 F. Supp. 3d 475, 483-84, nn. seven, 9 (1000.D. Tenn. 2018).

[82] Mendoza v. Garrett, No. iii:eighteen-cv-01634-HZ, 2018 WL 6528011, at *20 (D. Or. Dec. 12, 2018); Fowler v. Johnson, No. 17-11441, 2017 WL 6379676, at *viii (E.D. Mich. Dec. xiv, 2017).

[83] Bearden v. Georgia, 461 U.S. 660 (1983).

[84] Id. at 672 (emphasis added).

[85] Id. at 671.

[86] Id. at 665.

[87] Robinson v. Purkey, No. iii:17-cv-1263, 2017 WL 4418134 at *8 (M.D. Tenn. October. 5, 2017).

[88] Id. at *9 (emphasis added).

[89] Thomas five. Haslam, 303 F. Supp. 3d 585, 612 (M.D. Tenn. Mar. 26, 2018).

[90] Mendoza v. Garrett, No. 3:xviii-cv-01634-HZ, 2018 WL 6528011, at *19 (D. Or. Dec. 12, 2018).

[91] James v. Foreign, 407 U.Due south. 128, 138 (1972); cf. Thomas, 303 F. Supp. 3d at 627 ("Strange …does not have a novella's worth of subsequently Supreme Court opinions explaining precisely what the lower courts should construe it to hateful.").

[92] Significantly, the Supreme Court recently held in Timbs v. Indiana, 139 S. Ct. 682 (2019) that the Eighth Amendment's Excessive Fines Clause is an incorporated protection applicative to united states nether the 14th Amendment's due process clause. In its determination, the Court noted that "[t]he Excessive Fines Clause traces its venerable lineage back to at least 1215… Equally relevant here, Magna Carta required that economical sanctions 'be proportioned to the incorrect' and 'not be so big as to deprive [an offender] of his livelihood.'" Id. at 687-88 (internal citations omitted). Nether this reasoning, the private needs of the accused for economic survival must be considered in the analysis of whether a fine is considered to exist excessive.

[93] Thomas five. Haslam, 329 F. Supp. 3d 475,494 (One thousand.D. Tenn. 2018) (emphasis added).

[94] Fowler v. Johnson, No. 17-11441, 2017 WL 6379676, at *9 (Due east.D. Mich. Dec. xiv, 2017). In a few contempo cases in locations where public transportation is severely limited, such as in Montana and Michigan, plaintiffs have asserted their right to intrastate travel, challenge that these state statutory schemes assuasive for the intermission of a driver'south license due to unpaid fees and fines without enquiry into one's ability to pay deprived them of their constitutional right to intrastate travel. In support of this complaint, plaintiffs often cite Johnson v. City of Cincinnati, 310 F.3d 484, 495 (sixth Cir. 2002), noting that the court in Johnson held that the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment protected the right to "travel locally through public spaces and roadways." Id. This statement has all the same to prevail on the merits. The District Court in the Eastern Commune of Michigan noted that the Sixth Circuit a number of other Circuits have held that "denying an individual a unmarried mode of transportation – such as a car driven by the individual him or herself – does non unconstitutionally impede the individual's right to intrastate travel because in that location is no key correct to drive." Fowler, 2017 WL 6379676, at *vii.

[95] Mendoza, 2018 WL 6528011, at *24.

[96] The Fines & Fees Justice Heart maintains a clearinghouse of legislation, pilots and programs, litigation, and other developments. See The Clearinghouse, Fines & Fees Just. Ctr., (concluding visited Feb. 8, 2019).

[97] Id.; see also S.B. 1270, Reg. Sess. (Fla. 2018); H.F. 3357, 90th Leg. (Minn. 2018); South.B. 1013, Reg. Sess. (Va. 2018).

[98] Press Release, Office of Governor Ralph Northam, Governor Ralph Northam Unveils Upkeep Amendments for the 2018–2020 Biennium to the Joint Money Committees (Dec. xviii, 2018). Unfortunately, though the state Senate passed the neb, Republicans on a House subcommittee later voted to kill information technology. Run into Editorial Board, Virginia Inexplicably Killed a Bill that Could've Helped Thousands with Suspended Licenses, Wash. Post (Feb. 18, 2019).

[99] Personal Responsibility and Piece of work Opportunity Reconciliation Deed of 1996, Pub. L. No. 104-193, § 369, 110 Stat. 2251 (codified equally amended at 42 U.s.a.C. § 466(a)(16)).

[100] For example, the Alaska Supreme Court has noted that if its land'due south suspension provision "were applied so as to accept away the license of an obligor who was unable to pay kid support, it would be unconstitutional as practical in that example" because "there would be no rational connexion between the deprivation of the license and the State's goal of collecting child back up." State, Dep't of Revenue, Child Enforcement Div. v. Beans, 965 P.2nd 725, 728 (Alaska 1998). Additionally, a class activeness complaint filed earlier this month in the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Missouri alleges that a law that allows the land to suspend the commuter's license of any person who owes at least iii months' worth of kid support payments or at least $two,500, whichever is less, without first inquiring into ability to pay, violates parents' Constitutional substantive due process, procedural due procedure, and equal protection rights. Encounter Wright five. Family Support Div., No. 4:xix-cv-00398 (East.D. Mo. Mar. four, 2019).

Source: https://www.acslaw.org/issue_brief/briefs-landing/discriminatory-drivers-license-suspension-schemes/

0 Response to "The Effects of Suspending People License Peer Review Article"

Post a Comment